HOURS: TUESDAY-THURSDAY 12-6PM // FRIDAY & SATURDAY 12-8PM // SUNDAY 12-5PM // CLOSED MONDAYS

Vol. 43 - "The Return of the 18th Amendment"

Click here to read the PDF-formatted version

Book of Bertil 43

Is the return of the 18th Amendment possible?

From the "Temperance Movement" to the MAGA Movement:

An American History of Freedom and Contradictions.

INTRODUCTION

Wine, Politics, and American Fractures

In the United States, wine has always been more than just a beverage. Celebrated as a symbol of civilization and refinement, it has also been denounced as a moral threat and a cause of social decadence. The history of this drink in the country is inseparable from the great debates on freedom, identity and public morality. America was built on contradictory ideals: on the one hand the quest for individual freedom and cultural diversity, and on the other the temptation to regulate, even prohibit; This is perceived as a danger to social cohesion. The Temperance Movement, born in the 1820s, is the perfect example. Two centuries later, as new discourses of sobriety and public health, social conservatism, and productivity gain ground, a question arises: could the United States revive a modern form of Prohibition, like the one established by the 18th Amendment in 1919?

CHAPTER 1.0

Verse 43.1.01: From Jamestown to Jefferson:

Planting the vine as a political act

When British settlers founded Jamestown in Virginia in 1607, they didn't just come looking for new land. Their mission is also symbolic; to reproduce in America the cultures that embody European refinement: silk, olive oil, and especially wine. Producing wine is seen as proof of colonial success, a guarantee of civilization and prestige.

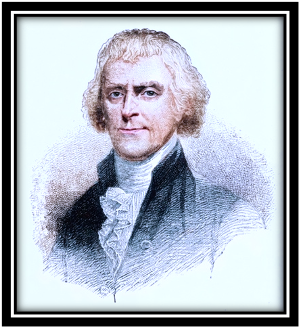

But the first attempts were bitter failures. European grape varieties are not resistant to local diseases. Despite repeated attempts, no cuvée worthy of the name emerged in the seventeenth century. It was not until Thomas Jefferson, the third president of the United States, that a real wine-growing ambition emerged. In Monticello, Virginia, he plants varietals and dreams. For him, wine is much more than a drink, it is a cultural and political marker. "Wine," he wrote, "is the drink of civilization," a refined alternative to the excesses of whiskey and cider, which were ubiquitous at the time. Jefferson saw in the vine the foundations of a republican identity that was "elegant, educated, turned towards the Europe of the Enlightenment". His vines never produced the wine he had hoped for, but his project posed a central question: "What culture and morality did this young nation want to embody?"

43.1.02: The Nineteenth Century:

Immigration, Abundance, and Excess

The nineteenth century was one of mass immigration. Germans, Irish, Italians, Jews from Central and Eastern Europe arrived by the millions. Everyone brings their traditions, their recipes, their alcohols. Wine, but especially beer and whiskey, became markers of cultural identity. But this diversity is coupled with unbridled consumption. In 1830, an American drank an average of nearly 7 gallons of pure alcohol per year, three times more than today's consumption. Whiskey, gin and cider flow freely, often easier to find than drinking water. Domestic violence exploded, poverty deepened, and the Protestant elites worried. "America drinks to the point of perdition," wrote a Methodist minister in 1828. It was in this social soil that a movement of unprecedented magnitude was born: The Temperance Movement.

43.1.03: The Temperance Movement:

Morality, Religion, and Political Crusade

Born in the 1820s, the temperance movement initially advocated only moderate consumption. But very quickly, the demand evolved towards total abstinence. For its activists, alcohol is "the source of all vices": crime, misery, and domestic violence, moral decline. Evangelical pastors, teachers, but especially women activists are mobilizing. The Women's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), founded in 1873, became a major force. Its members brandish Bibles in Saloons and organize protest marches. The Anti-Saloon League, formed in 1893, perfected political strategy by funding pro-Prohibition candidates and bringing down those who opposed it. Their slogan is simple: "Vote dry". Their success is also based on a religious climate. Evangelical Protestantism shapes a strict vision of morality. To suddenly drink is not only to harm oneself, but to threaten the entire social order.

43.1.04: The 18th Amendment and Prohibition:

Political Victory, Social Defeat

In 1919, after decades of struggle, the 18th Amendment was ratified. The following year, the Volstead Act clarified its application by specifying that the production, sale and transport of alcohol became illegal. The only exceptions were mass wine and some medical uses. Prohibition crystallized a profound confrontation: a rural, white, Protestant America imposes its law on a liberal, urban, immigrant, and cosmopolitan America. Taverns in large cities, perceived as centers of political influence by the Irish, Italians or Jews, were targeted. The big German brewers and distillers in Eastern Europe became targets. The prohibition of alcohol also serves to control the indigenous and African American populations, accused of social and racial "excesses" under the influence of drinking. The irony is that, despite everything, wine survived thanks to religion. Many wineries thrive on selling mass wine, while others offer "grape juice kits" with the tongue-in-cheek statement: "Be careful, don't let it ferment!"

CHAPTER 2.0

43.2.01: After Prohibition:

Wine between elitism and openness

Prohibition ended in 1933, but it left deep marks. For several decades, wine remained associated with an educated and white elite. The average American prefered beer or spirits, which have fewer social connotations. It was not until the second half of the twentieth century that wine emancipated itself from this image. The episode of the "Judgment of Paris" in 1976, where Californian wines surpassed French wines in a blind tasting, marked a turning point. California is on the world map, and wine is becoming a national pride. Today, American wine is not just about California. From New York to Oregon, via New Mexico, Texas, or Virginia, it has become a space for experimentation and identity reappropriation.

43.2.02: Diversity, Inclusion and Contemporary Struggles

The wine of the twenty-first century is also a field of social struggle. Queer wine bars make it a space of solidarity and celebration of identity. Producers proudly display their LGBTQ+ belonging, integrating this message into their marketing and events. Collectives like The Hue Society are working to put African Americans back at the center of the wine world. Networks, scholarships, events, so many levers to break the image of a universe reserved for a white elite. "Wine doesn't belong to a white elite, it belongs to all those who want to share it," says sommelier Tahiirah Habibi. Women are also gaining ground. The Women of the Vine & Spirits network and the Wine Women association encourage the role of women professionals in a sector that has long been dominated by men.

43.2.03: A new temperance? Chosen sobriety and social networks

Paradoxically, at a time when wine is becoming more inclusive, a new critical discourse is emerging. Inspired by well-being and public health, movements such as Dry January or the sober curious trend are appealing to millions of Americans. The numbers speak for themselves, in 2023, nearly 35% of young American adults said they had reduced their alcohol consumption, mainly for mental health and productivity reasons. On TikTok or Instagram, influencers accumulate millions of views by boasting a life "without hangovers, without regrets, more productive". This time, temperance is not driven by religion or morality, but by the quest for performance, health and personal development. There is no law prohibiting bars or spirits, but the cultural pressure is real. As historian Lisa McGirr (Harvard) sums up: "Each American generation is reinventing its battle against alcohol." But the question remains: After Prohibition and its excesses, is the United States moving towards a new form of temperance, gentler but just as socially restrictive?

CONCLUSION

Wine as a mirror of America

Wine in the United States tells a singular story. That of a Republic that wanted to distinguish itself from Europe and assert its refinement. That of a people crossed by excesses and moral crusades, to the point of banning alcohol in the name of virtue. That of a nation that, after celebrating California's victory over France, sees wine as a space of inclusion and diversity. Today, drinking wine in the United States is often more than just a taste pleasure. It is to be part of a complex political history, that of a country where every glass reflects the tensions between freedom and control, elitism and inclusion, pleasure and temperance. In short, wine is perhaps the most political drink in America, not because it sits in assemblies, but because it tells, with every sip, what it means to be American. So even if there are few indications in the official MAGA platforms or programs of a desire for moral control of the use of alcohol as in the 1910s and 20s, should we ask ourselves the question of the influences of the growing "Post-Reality" movement?

Mr. B

*Memorandum: My words and opinions in these newsletters are and would always be personal, and I intend to offend. I always accept that others have the full right and duty to challenge me, to argue, and, if it is necessary, excommunicate me from their beliefs (often dull and hollow) because I would act the same way if it were the other way around.

Powered by Lightspeed

Display prices in:USD