HOURS: TUESDAY-THURSDAY 12-6PM // FRIDAY & SATURDAY 12-8PM // SUNDAY 12-5PM // CLOSED MONDAYS

Vol. 46 - The origins of Thanksgiving in 1621

Click here to see the pdf-formatted version

The origins of Thanksgiving in 1621

A meal shared between English settler’s "Pilgrims" and Native Americans "Wampanoags"

Book of Bertil 46

The Real Story of Thanksgiving

Introduction

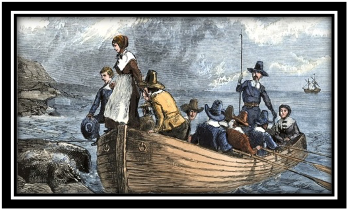

"The mythical story of the birth of America" begins in 1620, when 102 English colonists landed at Patuxet (future Plymouth) on the Massachusetts coast in late November and early December. It is often said that they were Puritans who dissented from the Anglican Church, but in reality, those who arrived in Plymouth were "Pilgrims": separatists convinced that religious reform in England had failed and that new communities should now be founded on more biblical foundations. Originally, only 35 settlers from the small town of Scrooby (Nottinghamshire) decided to leave, guided by William Bradford. However, due to the damage to the second ship, the Speedwell, other passengers known as "the Strangers" joined the expedition, bringing the total to 102 people on the Mayflower. Yet only 41 of them signed the Mayflower Compact on November 11, 1620, affirming their intention to settle in New England rather than Virginia.

CHAPTER 1.0

Verse 46.1.01: The Puritans vs the Pilgrims

The Puritans were religious reformers of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries within the Church of England, seeking to "purify" it of its Catholic influences. Some remained in the Church (the nonconformists), others left it altogether (the separatists), the latter being called "Pilgrims". The Pilgrims advocated individual justice and a clear separation between church and state. The Puritans, who were more numerous and arrived ten years later, in 1631, favored collective justice and wanted the government to strengthen religious laws.

46.1.02: A Decisive meeting

Upon arrival, the Pilgrims encounter the Wampanoags. Among them is Squanto (Tisquantum), a member of the Patuxet nation, who was captured by the English years earlier and sold to Spain, and who then managed to reach England before being brought back to America. He spoke English and became the indispensable intermediary between the two peoples. Squanto teaches them how to hunt, fish, grow corn, and survive. The first winter was terrible: half of the colonists died. Thanks to the help of Squanto and the Wampanoags, the harvest of 1621 was abundant. In the fall, to celebrate their survival and regained abundance, the Pilgrims organize a harvest festival and to thank God: This is the first celebration of Thanksgiving.

46.1.03: A celebration where the Wampanoags had not been Invited

Initially, the festival lasted two to three days and only concerned the colonists. Seeing the abundance and the revelry, the Wampanoags spontaneously joined them. Out of necessity to share food, the two groups hunt and eat together. This meal is described in the accounts of William Bradford, governor of the colony, and Edward Winslow, passenger of the Mayflower. The term "Thanksgiving" does not yet appear, but the spirit of thanksgiving is very much present.

46.1.04: From a local festival to a national holiday

These stories fell into oblivion until the 1840s and 1850s. In the meantime, New Englanders commemorate the arrival of the Mayflower every year. In 1777, amid the Revolutionary War, Congress proclaimed a Thanksgiving Day to thank God for supporting the fight against Great Britain. It was finally in 1863, during the American Civil War, that President Abraham Lincoln made Thanksgiving a national holiday, in the hope of reuniting and appeasing a bruised and divided nation. The date of Thanksgiving as recognized today (the fourth Thursday in November) would be set later, but it was in 1863 that the holiday officially became federal. So, what to put on the table and what to drink?

CHAPTER 2.0

Verse 46.2.01: Should the celebration be around a turkey?

Although the date of Thanksgiving was officially set for the fourth Thursday in November in 1939, under the presidency of Franklin D. Roosevelt, the turkey did not really become the emblem of the meal until the 1850s, thanks to the writer Sarah Josepha Hale. Certainly, turkey was already widespread in North America and consumed by the Aztec and Mayan civilizations, before being brought back to Europe in the sixteenth century by the Spanish. However, it was gradually becoming the central dish of the festivities. Abraham Lincoln wanted to make Thanksgiving a national holiday and a time to gather around a simple, nourishing meal that was accessible to all social classes of the young nation. Stuffed turkey (a relatively inexpensive and widely available meat) accompanied by mashed sweet potatoes, cranberry sauce, pumpkin pie and apple pie, became the emblematic menu of this democratic celebration. However, when you get closer to the original meaning of Thanksgiving, an acknowledgment of the abundance of land and sea, gratitude to the indigenous people for their help, and a spiritual thank you for the survival of the early settlers – turkey is by no means an obligation. The Pilgrims and the Wampanoags did not sit down around a single dish, but around a variety of foods: "ducks, geese, turkeys, fish, corn... ", as the accounts of the first settlers, notably those of William Bradford, recall. Thus, the spirit of Thanksgiving lies not in the turkey, but in sharing, abundance, and gratitude. The menu can therefore be free, generous and personal.

46.2.02: The dishes and wines

When the first English settlers set foot on these lands, they brought with them some puddings, apple pies and roast turkey. But soon, the richness of Native American traditions transformed their cuisine: corn, beans, squash, fish, game, berries and wild plants invited themselves to their tables. This cuisine based on the rule of the "Three Sisters" (corn, beans and squash) introduces, Sagamité (a corn-based soup), bannock cooked on stone, Succotash (a hot mixture of corn and lima beans), golden Johnny cakes (thin corn pancake) ... so many dishes that tell the story of this mix. More specifically on the coast, the New England Clam Bake celebrated the sea in all its generosity, but also game and fish cooked on embers or cedar planks, mingled with roots, mushrooms and wild berries, and even the fried green tomatoes, now a symbol of the South, bear the discreet trace of indigenous culinary knowledge.

46.2.01: The Meal

Here's why I'm offering you the opportunity to celebrate Thanksgiving with more traditional dishes and very appropriate wines from our Coast, if you are afraid or jaded of the Turkey Roast.

- Turkey fillet in herb coat

- Turkey Paupiettes with Mushrooms

- Seafood and Sweet Corn Gratin

- Goose Breast with Blue Berry Sauce

- Bannock with fried onion, pan-fried yellow perch and tartar sauce

- Sagamité végétariens familial

- Duck confit Sagamité

- Smoked duck cream of corn

- Stew of the three Native American sisters

- Fried green tomatoes

46.2.03: The Wines

Before European settlers arrived in New England, Indigenous peoples, such as the Wampanoag of Massachusetts, had no tradition of alcohol production. Without European bees, honey was scarce, making mead impossible. As for cider, it was inconceivable, since European apple trees did not yet exist on the continent. Local wild grapes, Vitis labrusca and Vitis riparia, were harvested to be eaten fresh, dried, or mashed. Occasionally, they would ferment by accident, but never with the intent of producing wine. Their bold, “foxy” flavor was a stark contrast to the European grape varieties that settlers would later introduce, along with beer, cider, and mead, beverages quickly adopted and favored over Indigenous traditions. Today, much of the wine produced in our region relies on hybrid clones of these two wild Vitis species, a fusion of local terroir and European grape varieties. By enjoying these wines, we celebrate not only the abundance of our land but also the memory of the plants and traditions that have shaped our viticultural landscape. It is a tribute to the historical and natural richness of New England, where past and present meet in every glass.

Here is a selection of wines available at the shop for your Thanksgiving celebrations, perfectly complementing the dishes I recommend.

Sparkling

- Saltbox Cider, Aged Dry Cider Honey Brut, Traditional method, Haverhill, MA

- Oyster River Winegrowers, Morphos Pet-Nat 2024, ME

- Westport Rivers Winery, RJR 2019, Westport, MA

- Domaine Finot, Pet-Nat Petit Verdot 2024, Turk Mountain Vineyards, Monticello, VA

- Westport Rivers Winery, RJR 2019, Traditional method, Westport, MA

- Sparkling Pointe, Blanc de Blancs 2019, North Fork of Long Island, NY

- Hermann J. Wiemer Blanc de Blancs 2019 Brut

- Standing Stone Vineyard, Finger Lakes, NY

White

- Westport Rivers Estate Muscat Ottonel 2022, Westport, MA

- Westport Rivers Estate Geisenheimer 2021, Westport, MA

- Lightwell Survey, Hintermen 2022, Shenandoah Valley, VA

- Lincoln Peak Vineyard, La Crescent Reserve 2024, New Haven, VT

- Lincoln Peak Vineyard, Frontenac Blanc 2024, New Haven, VT

Orange

- Marzae Wines Cornuta 2023, Orange wine, Acton, MA

- Lincoln Peak Vineyard, Amber 2024, New Haven, VT

Red

- Westport Rivers Winery "Westport Nouveau" Marquette 2024, MA

- Marzae Wines, Frondosa 2023, American red wine, Acton, MA

- Lincoln Peak Vineyard, Frontenac Noir 2024, New Haven, VT

- Shelburne Vineyard, Marquette Reserve 2021, Shelburne, VT

- Shelburne Vineyard, Petite Perle 2021, Shelburne, VT

- Oyster River American Red Merlot 2022, ME

- Hermann J. Wiemer Lemberger 2017, Finger Lakes, NY

- Standing Stone Vineyards Saperavi 2023, Finger Lakes, NY

But if you choose to celebrate in the traditional Thanksgiving culinary style, here are the wines I recommend complementing the various aromas and flavors of the different dishes on your table.

White

- Smith-Madrone Riesling 2019, Napa Valley, CA

- Hermann J. Wiemer Bio Riesling 2020, Finger Lakes, NY

- Bryn Mawr Vineyards Estate Riesling 2023, Willamette Valley, OR

- Scribe Winery "Ode to Emil No. XV" Sylvaner 2024, Sonoma, CA

- Left Foot Charley Wine, Auxerrois 2022, Old Mission Peninsula, MI

Rose

- Audeant Wines, Rose of Pinot Noir 2022, Willamette Valley, OR

- Arnot-Roberts, Rose of Touriga Nacional 2024, Luchsinger Vineyard, Big Valley County, Lake County, North Coast, CA

Red

- Jolie-Laide Wine, Gamay 2023, Sonoma County, Sonoma Valley, CA

- Vincent Wine, Gamay Noir 2021, Willamette Valley, OR

- Byron Kosuge, "El Galpon" Pinot Noir-Gamay 2023, Carneros, Sonoma County, CA

- Joseph Jibril Red Carbonic 2024, North Coast, CA

- Phelan Farm, Autrerment Red 2024, Phelan Farm Vineyard, Cambria, San Luis Obispo Coast, CA

- Kings Carey "To Market" Grenache Noire 2022, Santa Barbara, CA

Happy Thanksgiving

Mr. B.

*Memorandum:

My words and opinions in these newsletters are and would always be personal, and I intend to offend.

I always accept that others have the full right and duty to challenge me, to argue, and, if it is necessary, excommunicate me from their beliefs (often dull and hollow) because I would act the same way if it were the other way around.

Powered by Lightspeed

Display prices in:USD