HOURS: TUESDAY-THURSDAY 12-6PM // FRIDAY & SATURDAY 12-8PM // SUNDAY 12-5PM // CLOSED MONDAYS

Vol. 47 - "Mission"

Click here to see the pdf-formatted version

Once upon a time, our ancestors Vine

Zinfandel or Mission as “America’s Heritage Wine”?

Book of Bertil 47

Introduction

For decades, the Zinfandel grape has established itself as a convenient symbol of a wine supposedly born on American soil, reflecting a viticultural identity finally emancipated from Europe. This narrative widely promoted by the wine industry and marketing nevertheless conceals a more complex and unsettling reality. Behind origin myths, historical shortcuts, and romanticized Gold Rush stories, another vine preceded Zinfandel by more than three centuries. A discreet, rustic vine long overlooked and often scorned. By retracing the intertwined paths of these two grape varieties through colonization, geopolitics, genetics, and climatic constraints this account raises a fundamental question: What does it truly mean to speak of an “American heritage wine”? Is it the more seductive story, or the older one, that deserves this title?

CHAPTER 1.0

Verse 47.1.01: Zinfandel or Mission as “America’s Heritage Wine”?

Zinfandel is often presented as one of the emblematic grape varieties of the United States, yet its history is far from purely American. Originating in Central Europe, its genetic profile reveals deep roots in Croatia and Dalmatia, where it is known as Tribidrag or Crljenak Kaštelanski, as well as in Italy under the name Primitivo (sometimes referred to as Ragusa). The arrival of Zinfandel on American soil is nonetheless surrounded by myths and some sources even suggest its introduction by an Austrian prince around 1810 at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts. However, it is only between 1820 and 1830 that its cultivation is documented in New York State, likely on Long Island. But is this grape truly the first Vitis vinifera variety to have been commercially and successfully cultivated in North America, and more importantly, does it genuinely represent America’s viticultural heritage?

47.1.02: Viticultural Colonization in North America*

To properly contextualize this question, we must revisit the historical facts surrounding the conquest of the Americas.

The conquest of the South began in 1519 with Hernán Cortés, marking the incorporation of the territory into the Spanish Empire and the establishment of New Spain, Mexico. The conquest of the North followed in 1534 with Jacques Cartier, who claimed Canadian territory on behalf of France, leading to the creation of New France. It was not until 1607 that the first English colonies arrived in America, settling in Virginia, followed in 1630 by the founding of the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

47.1.03: The Colonists’ Vine

However, while Quebec where French colonies were established, lies around the 46th parallel, at the very edge of viable grape-growing geography, but its position between the 60th and 80th meridians place it meteorologically in a zone of severe winter cold, regularly reaching temperatures between 5°F and –4°F. Such conditions inevitably cause the death of European vines (Vitis vinifera). For this reason, it is impossible that the first vines developed from Canada.

As for Massachusetts and Rhode Island, although the climate was theoretically suitable for Vitis vinifera, colonists faced another major obstacle: the humid climate favored destructive fungal diseases, as well as the presence of phylloxera, an insect against which European vines have no natural genetic defense. It would not be until 1849 that the first hybrid grape adapted to New England conditions appeared. Only the specific situation of the North Fork of Long Island (New York) may have allowed for the early propagation of European vines on their own roots, such as Tribidrag, which is known to have been cultivated there as early as the 1820s.

In contrast, the border region between present-day Mexico and the United States lies between the 32nd and 37th parallels north. This warm, arid geographic zone features largely sandy soils, cool nights (sometimes rainy), and extremely hot days—conditions highly favorable to grape varieties originating in climates and soils similar to those of Europe. In addition, abundant water sources allowed for easy irrigation. As a result, Spanish grape varieties planted as early as the 1520s encountered no difficulty surviving.

47.1.04: Zinfandel: Is It Really the First “American” Grape?

The true rise of Zinfandel came with the Gold Rush (1848–1855), accompanied by the rapid growth of California’s immigrant population and a corresponding increase in demand for wine. Ill-suited to the climate of New England (though still found in very small quantities in some vineyards), Zinfandel thrived in the San Francisco Bay Area, benefiting from far more appropriate soils and climatic conditions. It was in California that it became America’s emblematic grape. Today, although overall production has declined significantly, the diversity of California Zinfandel is reflected in its many clones. These include so-called “heritage” or “old vine” clones such as the Palmer Clone or Wente Zinfandel alongside modern clones developed for commercial viticulture, including selections from Lodi and UC Davis. Together, they have contributed to the grape’s broad aromatic and stylistic range, from light rosé to concentrated, spicy reds.

CHAPTER 2.0

Mission: The Shameful Bastard of American Viticulture,

or Its True First Heritage Grape?

Verse 47.2.01: The First Colony

As early as the 1520s, Hernán Cortés encouraged the planting of Vitis vinifera on lands granted to colonists to reduce costly imports from the Iberian Peninsula. The first vineyards appeared in central regions and gradually expanded northward, where climatic conditions proved more favorable. Franciscan, Dominican, and especially Jesuit religious orders played a decisive role in this spread, or in the missions, the vine served both as a sacramental necessity and as a tool of agricultural organization, anchoring the colonial model. However, the development of colonial viticulture soon alarmed the Spanish Crown. Fearing direct competition with metropolitan wines, Philip II issued a decree in 1595 prohibiting the planting of new vineyards in New Spain, except for strictly religious use. This marked a major setback and placed wine production under close surveillance. Yet despite these restrictions, the vine did not disappear. It survived in isolated missions, particularly in Baja California, where Jesuits continued cultivation beyond the direct control of Madrid.

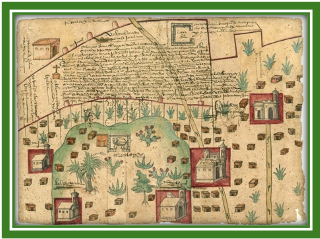

47.2.02: Geopolitics and the Territories of New Spain

Spanish Mexico refers to the period of Spanish colonization beginning with Cortés’s conquest of the Aztec Empire in 1521 and lasting until the reforms and independence movements of the early 19th century (Mexico’s independence in 1821). During this time, Mexico was part of the Viceroyalty of New Spain, created in 1535, which included present-day Mexico as well as much of Central America, including Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, El Salvador, and the southwestern United States: California, Texas, Arizona, and New Mexico. From 1530 onward, Spanish expansion moved north and west from central Mexico, establishing religious missions, presidios (military forts), haciendas, and colonial cities. In 1769, Spanish missions were established in California, following a colonial strategy extending from San Diego north to Sonoma and Mendocino. This expansion along the Pacific coast was no accident, it was dictated by geography, climate, and religious needs. Missions functioned as agricultural and religious hubs, each requiring wine for Mass and to sustain local populations. The vine was propagated by cuttings transported between settlements, while Indigenous peoples that had converted and were employed by the missions were settled in coastal valleys, where viticulture could be easily integrated into an agricultural system organized by missionaries.

47.2.03: Protection Against the Invader

New Spain sought to secure its northern territories modern-day Mexico and California because the California coast was sparsely populated and vulnerable, while English forces were beginning to establish trading posts and colonies in northwestern North America (British Columbia, Alaska) and along the East Coast (the Georgia colony and expansion toward Louisiana). Fearing foreign invasion or territorial claims, Spain created a network of missions along the California coast, from San Diego to Sonoma, aimed at the sedentarization of local populations and asserting Spanish presence through permanent installations. These served to control strategic valleys and create defensive points in case of foreign attack.

47.2.04: The Mission Vine as Part of the Colonial Arsenal

The Mission vine produced the sacramental wine essential to the missions. It also served as tangible proof of agricultural colonization, demonstrating that the Viceroyalty of New Spain had successfully implanted European crops in these “contested” lands. In other words, the Mission was not merely a grapevine, it was a living symbol of Spanish presence in the face of rival colonial powers.

47.2.05: The Grape and Its Origin

DNA research conducted in the early 2010s established that the Mission grape was known in Spain as Listán Prieto, in Chile as País, in Argentina as Criolla Chica, and in Peru and Bolivia as Negra Criolla or Criolla Negra. It was the first European grape variety to be durably established in New Spain. Likely introduced in the 1520s, it was chosen for its robustness and adaptability. Undemanding, drought-resistant, and tolerant of poor soils, it quickly acclimated to the often-extreme conditions of central and northern Mexico, as well as the entire California coast, where it became the backbone of colonial viticulture. Throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, the grape known as Mission remained virtually the only variety cultivated in New Spain. Only with the end of colonial rule did its role begin to change, yet its legacy remains inseparable from the origins of wine in North America.

After Mexican independence in 1821, colonial restrictions were lifted, but viticulture did not immediately flourish. Mission was already perceived as rustic and low-quality compared to the new European varieties introduced in the 19th century by Italian and French immigrants. Gradually replaced by grapes deemed more “noble,” both in Mexico and California, Mission declined sharply by the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The phylloxera crisis, agricultural industrialization, and political upheavals, most notably the Mexican Revolution (1910–1917), accelerated its removal. The grape survived mainly in isolated vineyards, often on their own roots, cultivated for family or religious use outside commercial circuits.

47.2.06: The Revival of a Heritage Grape

By the mid-20th century, Mission was considered obsolete. Long used for sacramental wine, sweet wines, or household production, it was increasingly uprooted in favor of varieties considered better suited to modern winemaking. Its high yields but simple aromatic profile made it unattractive at a time when the American wine industry sought prestige and parity with Europe. After the end of Prohibition (1933), American viticulture entered a period of profound transformation. In this shifting landscape, Mission and Zinfandel came to embody two opposing trajectories that reveal changing tastes and market priorities. As the direct heir of mission viticulture, Mission was largely marginalized, while Zinfandel gradually asserted itself as a symbol of California wine. However, at the turn of the 21st century perceptions of Mission began to change amid a broader rediscovery of historical grape varieties and heritage vineyards, and producers and historians alike renewed their interest in this foundational grape. In both Mexico and California, old parcels were identified, studied, and sometimes vinified separately. Long a symbol of austere colonial wine, Mission is now viewed as a living witness to the viticultural history of the Americas linking five centuries of agricultural and cultural continuity.

CHAPTER 3.0

It therefore becomes clear that the true first emblem of American viticultural: Heritage Vine is the Mission grape, not Zinfandel.

Verse 47.3.01: Listán Prieto: History and Synonyms of a Foundational Grape

Listán Prieto is one of the oldest and most influential grape varieties in global viticultural history, though it long remained in obscurity. Originating in Spain, it is now recognized as the first European grape to be durably established in the Americas. Its trajectory mirrors Spanish colonial expansion and the spread of viticulture beyond Europe. Its origins likely lie in southern Spain, particularly Andalusia and the Canary Islands, where it is documented as early as the 15th century. Rustic, productive, and relatively drought-resistant, it was well suited to hot climates and poor soils. Although Mission (American) and Listán Prieto (Canaries/Spain) now show slight phenotypic differences resulting from centuries of geographic isolation and propagation by cuttings or seeds, they remain expressions of the same original cultivar. Broader genetic analyses of ancient grape varieties in both South and North America have demonstrated that Mission (United States), País (Chile), and Criolla Chica (Argentina) are all clones or synonyms of the same Listán Prieto genome introduced by Spanish missions in the 16th century. These findings confirm that the vine used by Spanish missionaries for sacramental and agricultural purposes in the New World originated in ancient Spanish vineyards, even though the grape has nearly disappeared from the Iberian Peninsula today.

47.1.01: Selection and Preservation of Historical Clones

University of California, Davis; catalogs and preserves several genetic selections of Mission within its Foundation Plant Services (FPS) program, sourced from very old California vineyards. For example, clones such as Mission 17 originating from an old Santa Barbara vineyard planted around 1887 have been studied and preserved.

Known Mission clones and selections maintained by FPS include:

- Mission 02: Originating from a California vineyard near Woodbridge, sourced from old cuttings reported around 1959.

- Mission 06: Collected around 1964 from an old vineyard in Calaveras County, California.

- Mission 07: A historic California clone, with precise details varying by certification source.

- Mission 17: A very old and historically significant clone from a Santa Barbara County vineyard planted around 1887. It is among the oldest authenticated Mission clones preserved by FPS and used for restoration and replanting.

Conclusion

An examination of historical, agronomic, and genetic evidence leaves little room for doubt. While Zinfandel brilliantly embodies the modern success of California viticulture, it is neither its origin nor its foundation. Long before Zinfandel’s documented arrival in the 19th century, Listán Prieto had already shaped a continuous viticultural landscape from colonial Mexico to California’s valleys integrated into missions, religious rites, and the territorial strategies of New Spain. Long relegated to the status of a utilitarian, even shameful grape, Mission now emerges as a living witness to five centuries of agricultural and cultural history. To acknowledge its role is not to diminish Zinfandel; it is to accept that American wine heritage rests on older, more complex, and sometimes uncomfortable foundations.

So, the question remains: is wine America ready to recognize its true founding grape, even if it does not align with the story, it has long

told itself? For my part, there is no longer any doubt.

Mr. B

*Memorandum:

My words and opinions in these newsletters are and would always be personal, and I intend to offend. I always accept that others have the full right and duty to challenge me, to argue, and, if it is necessary, excommunicate me from their beliefs (often dull and hollow) because I would act the same way if it were the other way around.

Powered by Lightspeed

Display prices in:USD